Transcript

[silence]

Thank you once again

for agreeing to talk to us.

To begin with, could you please

tell us your name and surname,

date and place of birth?

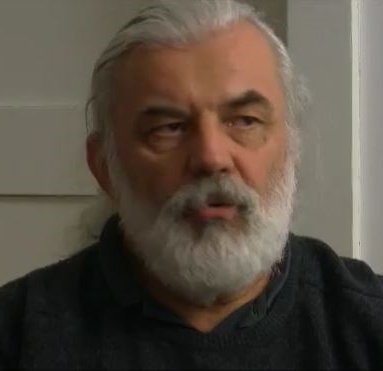

My name is Srđan Dvornik. I was

born on May 24, 1953 in Šibenik.

Could you tell us something about your

occupation and line of work today?

Formally speaking, I am a

professor of sociology

and philosophy with a degree

in political sciences.

I mostly work as a translator,

but I also engage in different consulting

services, analyses and studies

related to these social,

non-profit topics

as well as problems and activities

related to human rights,

democratic initiatives and the like.

Could you tell us something

about the origin of your family?

A brief outline of their history?

Although I have spent more than

90 percent of my life in Zagreb,

the entire family history

is tied to Dalmatia.

Both of my grandmothers,

my paternal as well as my maternal

grandmother, come from Brač.

One of my grandfathers

comes from Split,

which is where my surname,

Dvornik, comes from.

My other grandfather

comes from Starigrad on Hvar.

In the period between

the two world wars,

due to the economic

circumstances,

they moved a lot, looking for

and following their work,

so they lived in

various places in Dalmatia.

In the 1930s, they somehow

ended up in Šibenik,

which was also where

my parents met later on.

To your knowledge,

was your family in Šibenik

in any way affected by WWII?

Or took part in it?

My father's family was more

actively involved.

I can't recall what my grandfather

was doing there at the time.

But his health significantly deteriorated

due to all the circumstances of the war.

He never recovered, he suffered

from it until his death in 1955.

And my grandmother

was involved in some illegal work.

Once, she told me about carrying some

hand grenades in a shopping bag,

grenades which

some younger boys,

including my father and his brother,

had stolen from the Italians.

These had to be

smuggled to the partisans.

My father and his brother,

as members of the League of Young Communists,

also took part in

illegal work in Šibenik.

Mostly intelligence, but sometimes some

weapon procurement such as this as well.

But, mostly, thanks to their

fluency in Italian and German,

they gathered information, even

through contact with ordinary soldiers,

and passed it on

to the partisans.

Did anyone in your

family get hurt in WWI?

Not through direct

participation in the fighting,

nor was anyone killed in

the battles or the bombings. No.

My mother's brother joined

the partisans when he was quite young.

I'm not sure, he was

a kid, still very young.

He was 16 in 1941, but he

had joined the partisans very early on.

After the war, he even retained

an officer position in the JNA air force.

He was wounded, but not gravely,

nor did it have any lasting aftereffects

such as disability for him.

I would estimate that my family

was affected by the war as much

as any other one, having

an average involvement in the war.

It could hardly happen that somebody

was not at all affected by the war.

After all, Šibenik was targeted

by some heavy bombing as well.

But my family hasn't been

severely affected by the war.

What memories do you

have of your early youth?

Were you still living in Šibenik,

or did you live somewhere else?

I don't really have any memories

of Šibenik from that time of my life.

I was born there, but, for a little

while, when I was still a baby,

I stayed with

my grandmother on Brač.

Then, as my parents went to work

in Lukavac, and later on Tuzla,

that was where I spent

the first 4 years of my life.

That was also where

my brother was born,

when I wasn't even 2 years old.

In Lukavac.

That's close to Tuzla.

And then, in 1957, when I was 4 years old,

my parents found work in Zagreb.

Then they moved here

and have lived here ever since.

I have no particularly prominent

memories from that time.

When you're a very small kid,

it's very difficult to discern

anything as specific to your area.

Everything is new to you when

you're a kid, wherever it happens.

I do remember one thing, and it's quite odd

that I do, since I was so young.

I remember something that would today

be designated a cultural shock.

When I arrived to Zagreb,

I was under the impression that

the people here were speaking

in a completely different language.

That is, that my speech

was foreign to them.

Granted, my combination of

Dalmatian and Bosnian speech

did have some common ground

with this Zagreb kajkavian speech,

but it also had

so many differences

that, for a while,

I had trouble adapting to it,

as well as trouble

with basic communication.

What was your family's attitude

towards ethnic identity?

And how did it reflect

on your upbringing?

My parents were first and foremost

truly staunch Communists.

They understood Communism

as a historical project

worth advocating, something that

could bring about true equality,

not just formal, but social

and every other kind of equality as well.

Their position was

quite pronounced,

in a way that

consciously departed from

all divisions based on

national or ethnic affiliation.

It didn't adhere to some

surrogate affiliation with a quasi...

It didn't follow

this pattern,

finding surrogate affiliation in

Yugoslavianism or something like that.

They simply maintained

that it was pointless

to acquire this kind

of identification

as something

marking one's identity.

One has many disagreements

with one's parents.

I may have sometimes been

too much of an anarchist,

or too radical a

leftist for them,

but we never disagreed

on this particular point.

Nor was it

an imposing ideology.

I have seen it in people

whose background was in families

that highly valued

their national identity,

that is, nationalist families,

or people

whose families opted for

true Yugoslavianism

as an identification,

an affiliation much like

national identification.

As much as this is forgotten today,

it was also very much present.

I know that my coevals

had many great conflicts

and falling-outs

with their parents

in these kinds of families.

My parents' attitude was

unobtrusive and inclusive,

which made it easier

for us to get along.

Whether I was marked by it

as heritage or as my own choice,

I can't say or know.

In any case,

it has ancient roots.

Just like I was already the third generation

of religionless people in my family.

Your family had

no religious identity?

That's right. Beginning

with my grandmother.

The same grandmother

who took part

in the illegal resistance in the war,

she was completely

indifferent towards it.

It took hold and

continued from her on.

I know that my maternal

grandmother was a believer.

But she belonged to the

best kind of believers.

Those people who believe in God in a way

in which one believes in something good.

In positive values.

She used to say:

"It makes no difference

that you don't go to

church and don't pray.

I pray for you as well."

And she never would have done

what grandmothers used to do

in these intergenerational conflicts,

christening their grandchildren

in secret or things like that.

It was quite similar to the relation towards

national identification in my family.

A kind of very pleasant,

peaceful coexistence

between those who

believe in something

and those who don't believe

in anything otherworldly,

who put their faith in the

values of this world.

Did you notice any

differences between yourself

and your coevals when it

came to national identity?

Were there any

conflicts or disagreements?

Not until1970.

It simply wasn't a

topic of conversation.

And when I reminisced...

In elementary school, for example,

which I attended until 1968,

there were names and surnames that we

would later clearly recognize as Serbian.

Or as Bosniac.

Several Macedonians, etc.

But I only remember it

when thinking back on it.

Ah, yes, this name and surname

is actually connected to it.

It simply wasn't

an issue at the time.

Nor was there an attitude such as:

"I don't care who comes from where."

No, I wasn't even aware

that there was such a thing

as being from here

rather than there.

Or anything similar.

The only difference I noticed

was that as a Dalmatian,

formed in Bosnia through

primary language socialisation,

I arrived to Zagreb and

noticed a difference in speech.

Consequently, I saw that some differences

were based on where you were from.

And later on one notices that,

at the time, in the 1950s,

most of these malicious jokes

based on collective stereotypes

about Dalmatians were in

circulation in Zagreb.

Then, of course, as I somewhat

belonged to that category, I noticed it.

But these national, ethnic,

fratricidal differences from Yugoslavia, no.

I discovered those just

before I came of age.

You said it was 1968.

- 1970.

I mentioned 1968, that was when

I finished elementary school.

Why 1970?

Because that was when

this wave of nationalism,

which was induced

from on high, began.

And then it suddenly

became a big deal.

A year later, at the time of

the census in the spring of 1971,

all of a sudden everyone was very

outspoken in declaring themselves.

The discourse resembled

the one surrounding

political elections nowadays.

As if it was a matter

of political alternatives.

I was appalled by

the meaning of nationalism

in everyday life, in political life and culture,

actually, wherever you turned.

At the level of

totalitarianism in this ideology.

That was what I experienced.

It was one of my first

encounters with politics.

When you're a teenager,

you hear many things,

but you don't feel

like they concern you.

You were 18 in 1970, 1971?

You were already up to date

with political developments.

That's right. In 1970,

when I was about to turn 17,

I first glimpsed politics as

an arena where something

that affected society, lives,

relations was taking place.

And my first impression

was shockingly negative.

What did you think of the

events centering around MASPOK,

that is, the Croatian Spring?

Yes, this romantic appellation;

the Croatian Spring.

It's one of these lying

formulations such as

the denomination of war

veterans as defenders,

such as the Homeland War,

such as the national liberation struggle,

all these things,

this beautification in reverse.

I experienced it, even nowadays,

when I had the opportunity to think

more critically about it and read many things,

I experienced it as

an incredible compound of

an ideological change induced from on high,

from the highest political echelons,

and a mass mobilisation from below.

This rarely succeeds.

It's probably the biggest fantasy

of every power-wielder.

To start a process which is

actually their own score-settling

of one fraction against another.

And manage to mobilise

mass support for their side.

And I wonder,

at least in our parts,

whether anything other than

nationalism can trigger this.

Can people be mobilised

by any other cause?

Mass movement, that's

another deceptive expression.

That was a mass movement,

but it was induced by the

authoritative Party leadership.

And it began as

a rupture on high,

in the leadership of the

League of Communists of Croatia.

During which a clear signal

was sent out to the public,

indicating that nationalism

was no longer a bogeyman.

And that displays of nationalism

would go unpunished.

This happened 3 years

after the first public event

that brought the problem

of nationalism, so to say,

into the open.

And that was

the Declaration on

the Status and Name of the

Croatian Literary Language.

At the time, all these

authoritative Party entities

had condemned it as nationalism.

And I do believe that was

the motivation behind it.

But there were real problems

regarding the then language policy

which was, unlike the

later separatist, truly unificatory.

No good ever comes out of

politically forcing a process

that is not already at work

in the life of the language.

In 1967 nationalism was

still harshly condemned.

Beginning with the 10th conference

of the Central Commitee of the

League of Communists of Croatia, which

took place in February 1970,

a signal was sent to society,

indicating that the main problem

was no longer nationalism,

but something that they

designated unitarism.

You are referring to the score-settling with Žanko?

- Yes.

And then eveything took off.

There was even

a kind of liberalisation.

It can probably

be interpreted as

the whole Yugoslavian regime

entering a kind of liberalisation.

An attempt to maintain the

system through a kind of reform.

So there was, first and foremost,

the liberalisation of the economy.

Which only led to greater instability.

They were even scared by

its results because a transition to

full market economy

doesn't happen just like that.

It claims victims.

But it also brought about

a struggle for influence between

various republican

Party leaderships.

As well as clashes regarding

the distribution of power and resources

between the League of Communists of Yugoslavia

and the leaderships of the republics.

And the leadership of the

League of Communists of Croatia

with Savka Dapčević Kučar.

Public support came in handy

in this struggle, of course.

For a while, they believed,

and managed to pull it off for almost 2 years,

that they would be

able to restrain it.

That they would be able to keep

this movement from below,

without it ever escalating

into a real movement,

because they would be

heading it all along,

keeping a tight rein on it.

Thanks to this desire to empower

the support from below

many things had to be

released and liberalised,

so the number

of publications

published by Matica hrvatska

and some cultural institutions

increased.

Croatian Weekly (Hrvatski tjednik)

is the best known.

And in these publications

there was an impression

of increased freedom.

But, once again, it was the

freedom of the unison

within this nationalist

politics and ideology.

For example,

at the University,

where there was an active

minority struggling against this,

it was violently shoved

aside when necessary.

Friends of mine who were already

studying at various faculties,

who saw and experienced it themselves

told me about some of these events.

I even saw some of them.

Not the violent ones.

But, for example, the beginning of

the student strike late in 1971.

You were already in Zagreb?

I was in Zagreb since 1957.

- You were a student?

No, not yet, but everyone

was talking about it.

And anyone could come

to various happenings.

I was in the hall of

the Student Centre

when the Student Alliance

of Croatia made the decision

to extend the strike

from Zagreb to all of Croatia.

And it was plain to see that

there was practically no space,

that there was no pluralism

and no democracy there.

It was an unisonous expression of

support to one and the same thing.

The only friction appeared

because the student leaders

believed that the Party

leadership might betray them

by not going the distance

in a radical manner.

The symbol of the dispute was the

matter of the foreign bills of exchange.

A part of Yugoslavia's economy

was capable of export.

Perhaps not ready to

withstand full competition.

But they could do business

in the half-sheltered

markets of eastern Europe or

the nonaligned countries.

There was some

income from foreign trade.

From export.

And the main apple of discord

was the matter of where

these foreign bills of

exchange would wind up.

And, rather indicatively,

the issue was only whether

they would end up in Belgrade

or Zagreb, or Ljubljana,

depending on the viewpoint

of the speakers.

But the issue wasn't whether

they would end up in

the companies that had

actually produced them.

No, it was clear that they were at

the disposal of a political unit.

The only issue revolved

around whether it was

going to be a federal

or republic unit.

In this radicality of

the struggle for our

foreign exchange bills,

the students believed that

the Party leadership would stop

upon reaching a certain point.

Which was, of course,

a very realistic assessment.

Did you witness the clash

of the student strike?

I saw some of it on the TV.

Granted, there was

no live coverage.

And people talked

about it. I saw.

As I lived in the vicinity

of Cvjetno naselje,

then I saw all these police units

surrounding the student dorm

in Cvjetno naselje.

I went to school there up

until 3 years before that.

It was my neighbourhood,

where I had many friends.

I didn't witness the melees

on the Republic Square.

My friends told

me about it.

Some of them took

part in it as well.

All of a sudden you discover

differences in these coeval groups.

Some of them were into this student

nationalist movement heart and soul.

So they joined it even though

they were still in high school.

Later on, it became

clear that some

vulnerable points of the regime

had been encroached upon.

Because the clash was brutal.

Of course, my claim that there

wasn't even a shred of democracy

in this nationalist movement

doesn't rule out the contention

that there was no trace of democracy

nor respect for political freedom

in the way the movement was dealt with.

A repression much like the one

in Belgrade 1968 ensued.

Very many people ended up

in prison, many lost their jobs, etc.

When did you enrol

in the University?

Right after that.

In 1972.

It was immediately after the

student strike had been crushed.

What was the atmosphere

at the faculty like?

Personally, at the time

I wasn't aware of the level

of this horrible repression.

That sort of repression

belongs to the arena of

the persecution of the so

called delict of thought.

Personally, as I saw this

nationalist movement as

very repressive and exclusive.

My girlfriend's friend

was beaten up in late 1971.

Because some students,

strangers she was passing

by in the street,

told her: "Merry Christmas."

She replied: "I don't celebrate that."

And they beat her up.

And that wasn't

an isolated case.

So I was quite pleased that

all these nationalists

were removed from

the public eye.

Afterwards, I learned how many

people had ended up in prison

just because of their political standpoint

or some words that they said.

And how unjust this was.

But, since I came to study at the

Faculty of Philosophy and Social Sciences,

where a specific

atmosphere prevailed,

the politics that I saw

in action there were

the very lively activities

of a leftist group

that was very critical

towards the regime,

but from a completely

different standpoint,

a group that was equally critical

towards nationalism,

and believed that the

kind of political system

that was created under the

designation of socialism

was still reproducing

the class system.

Meaning, a part

of society was still

doing most of the production,

they were the exploited.

And the working class still existed.

The only difference was that pure capitalists

were replaced by, as we called them,

the red bourgeoisie.

That was a section

of politically active students.

Even organised.

However, not autonomously, because

that wasn't possible at the time,

but through the

Student Alliance.

Until they broke us up.

It partly relied on

the heritage of what

the student movement of

1968 had argued for.

Did you join this group?

- Yes, of course.

What were your activities?

What did you do?

We organised some panels.

The nice thing

about the faculty

was that it enabled you to bypass

many technical and legal obstacles

that you were normally

surrounded by in such a regime.

To organise a public panel on a political topic,

which is nowadays so easy to do

that probably nobody

is going to show up

unless the subject is

particularly stormy,

sensitive and controversial.

At the time you couldn't do it at all

unless you already had an institution.

Since the second half of the 1960s,

a recognised public discussion always

took place at the Student Centre,

at 5 minutes past 8 pm,

when the halls would be

overflowing with people,

a discussion with

an amazing turnout

because it was the only place that

the Party didn't completely control,

neither in topic nor in

the choice of speakers,

and other matters

were discussed.

Which topics were

covered in these panels?

Right now,

I can only think of

one where our late philosophy

professor Branko Bošnjak

spoke to Mijo Škvorc,

forming a dialogue between

a Marxist and a Christian.

Without any censorship, the man

who was in the Marxist position

was one of the

Praxis dissidents.

And the man in the Christian position

was not a dissident within the Church,

but he didn't have to censor

himself out of fear from the regime.

That was the liberalisation

of the late 1960s.

We organised panels

on all kinds of topics.

I can't even

think of them now.

We organised some culture days,

as alternative as anything could get then.

It was a storm in

a teacup, really,

if the whole society is

taken into consideration.

But it was very important to us.

At the Faculty, we had fervent

disagreements with the Party organisation.

We leaned towards

social liberalisations.

Truth be told, in all fairness,

none of the nationalists or the leftists

ever mentioned some basic

hallmarks of liberal democracy

such as the freedom

of political organisation,

direct elections, political pluralism

or anything of the kind. No.

We advocated

social justice.

And the nationalists advocated national

independence and autonomy, etc.

What did you think of the

political system of Yugoslavia?

Of SFRJ?

I thought it was utterly

wrong to control

the social life, intellectual

and cultural activities

and exchange, the

expression of ideas, etc.

through the Party

power centre,

regardless of whether this centre

was Yugoslavian or Croatian.

But I have to admit that I was

a bit slow in this matter.

Until 1990 I didn't believe

that a multiparty system

was the solution.

I thought that no-party

democracy might work.

Meaning that people would choose their

political representatives according to

their options, the views and

beliefs of the representatives, etc.

In the framework of a party, or?

- No.

Without any frameworks.

However, I just anticipated the

sceptic attitude towards political parties

that everyone has today.

At the time, I had read enough of

what was written within the realm of

political sciences to have

no illusions about parties

truly representing any

social groups or their interests,

not even in countries with

longstanding democratic tradition.

Those were newcomers.

The Green Party in Germany

was still a very new arrival.

Other than these

exceptions of parties

that really grew out of

grass roots social movements,

there were no illusions

about parties.

Even then, in the political

disputes of the 1970s,

we believed that

a desirable alternative to

this sclerotic political system

could be found in a radical

interpretation of self-management.

As a kind of grass roots democracy

in the production sphere.

That it could be extended to

a system used in all social relations.

In any case, the authority

of the Party was something that...

Granted, our concepts were not very

well-thought-out and elaborated at the time,

but they were a response.

We reacted, assumed

a reactive position.

The reign of the Party enabling

narrow-minded mediocrities

who cared only about staying

in power and controlling everything,

the system that gave them

the opportunity to function

in the only way they knew how,

by controlling whatever they could

and smothering

what they could not,

that needed to be

brought down at any rate.

Did you see any exceptions

within this Party system,

anything you thought of differently?

- No.

Not party hacks, but...

- No.

The very few exceptions

were some intellectuals

who believed that they could,

through taking the Party at its word,

holding it to its program, holding

it to its highest declared objectives,

accomplish something through it.

All the Praxis dissidents

were once members of the Party,

but they were all thrown out.

There were some others who were

not involved in such radical conflicts.

But expecting someone enlightened

within the Party itself was perhaps

a naive illusion one could have

harboured in the very beginning.

But it wasn't a belief,

it was story you could buy

until you had a closer look.

But things were

more or less clear.

Especially in light of the reaction

that the mid-1970s saw

in response to the danger

brought about by the early 1970s

and these nationalist movements.

That is, no, there was a nationalist

movement only in Croatia.

But the leadership of the Leagues of

Communists of Serbia and Slovenia,

without any mass movements,

also tried to gain more independence.

Were they replaced as well?

Those in Serbia were condemned

as liberals and replaced.

In Croatia and Slovenia they were

condemned as nationalists and replaced.

But, at the time, I didn't know much

about this liberal Serbian leadership.

But there were some really

decent people there.

Which was exactly why

they couldn't hold out.

Then, during the 1970s, some

changes were made in the Constitution.

Changes formally marked by

introduction of the

Law on Associated Work

and the creation of the

delegate system.

Through which the regime

itself tried to undergo a reform

including the inauguration of

an important element of liberalisation,

decentralisation.

And the establishment of a formal

mechanism which indicated that

the so called working people and the

citizens below were actually the ones

making the decisions on everything,

choosing the people to decide, etc.

But so many complications

and so many levels were involved

that it wasn't immediately clear,

except to several critical thinkers,

I remember Žarko Puhovski

immediately saying that this

was going to be the

meaning of these changes.

But, gradually, anyone

who eyed it critically and

at all meticulously realised

that the endless

complications of the system

allowed more maneuver space

for the Communist Party,

which could then control everything

through bypassing the system,

and decide on everything in the end.

As for the decentralisation

that the 1974 Constitution brought

by giving the republics

more autonomy...

By the way, the districts

had much more autonomy.

Districts were little countries.

I don't know how many

people remember it today,

but the districts had

their own police.

It wasn't called 'policija',

but 'milicija'.

But it wasn't directly under the jurisdiction

of the republic, it was tied to the district.

A great decentralisation

took place.

But excuse me, I

interrupted you when

you were about to

pose a question.

Do you believe that the 1974 Constitution

sufficiently weakened the Federation

by giving greater autonomy to the republics,

which, in the end, through different

interpretations of the Constitution,

led to the breakup

of Yugoslavia?

It didn't.

Of course, it would be too neat,

too simple, and too easy to interpret

if changes in normative

acts would lead to

in-depth social

and political changes.

But it expressed and

created these options.

A joke from a much later time in the 1980s

describes this excellently.

When we began

to go through

increasing economic difficulties,

and even went into regression,

which was then erroneously

designated a crisis.

The system wasn't based

on economic efficacy,

so the loss of economic efficacy

didn't bring it into a crisis.

But it did create hardships

and dissatisfaction.

Here's the joke:

How come everything is going so badly

and the nationalists are quiet?

In the 1980s the system

was developing cracks on all sides.

And its enemies, the nationalists,

weren't taking the opportunity to speak.

The answer was:

They're confused.

All they had ever asked for was introduced,

and still everything was going wrong.

The leadership,

the then still unified

leadership of the Party,

in which the most active man

was not Tito but Edvard Kardelj,

drew a lesson

from seeing

that the effective, successful

nationalist mobilisation

was possible and strong.

And employing the good

old corporate paradigm,

rather than trying to suppress the differences,

it decided to incorporate them.

They introduced the postulate

of the mass movement,

the republic as a

national state.

And in these damned Balkans this 'national'

does not have the civilised meaning

of a community of all citizens,

rather, it denotes ethnicity.

Which means that Franjo

Tuđman wasn't the one

who first declared Croatia

a country of Croats,

it was Tito, Kardelj and Bakarić.

This Constitution did and

did not weaken the Federation.

This Constitution strengthened the

Party leadership with Tito in the forefront.

Because a system in which decisions

are reached through a consensus

of the republic and district heads,

which is what has already been set,

when 8 of them have to make a decision,

important political decisions,

and they have already began to

publicly present themselves

as representatives of

particular interests,

later on, the talk of this nonsense

called identity would begin,

special interests of their

own federal units.

Then there is no such thing as

compromise, much less unison,

without an authority

to put it all in order.

And when the authority

disappeared in 1980?

Ah, yes. But while he was alive,

it was very productive for Tito's reign.

The federal centre of power

was strengthened by the decentralisation.

The European Union is a good

example of the same problem.

They're also having

trouble with this.

The density of their relations

is much larger than the

integration of their political system.

A system still partly

relying on the consensus

of the representations of the national

governments of the member states.

In Yugoslavia, in a situation in which you

had an authority outside the system,

Tito was the president,

but, formally, there was the

presidency of the Party

and the presidency of the state,

consisting of an equal representation

of all the republics and districts,

an external scenic arbiter such as Tito

had a very wide field to manouver.

His hands were completely untied

to act as the integralist factor

for the very reason that the

formal system didn't allow,

didn't guarantee integration,

and very often didn't even

provide an opportunity for it.

That's why the

turnabout took place.

When he died, the decision-making

jumped into a greater deficit

than the accumulation of revenue.

Profit wasn't recognized

at the time,

what mattered was the accumulation

of revenue and the production,

enabling people to get everything

they needed for a life of quality.

That was collapsing, but the political

decision-making was in a greater deficit.

So it was the creation

of a system that served,

it was crisis management.

It enabled system

to get through

the crisis of the nationalist

decentralisation,

to abolish it as something autonomous

in a properly Hegelian manner,

preserve it and raise

it to a higher level

in terms of the factors

within the system itself.

But it was possible to

run it only through

a personalised

political authority.

And without a persona, without Tito,

it suddenly entered a crisis.

The interesting thing is, pardon me,

I'd like to just add one more thing,

the interesting thing is that,

I have my own understanding of it,

but I do think it's something

still worth discussing in

the collective

understanding of our past.

The interesting thing is that the system

didn't collapse in 1980, but in 1990.

That's the big question.

So, you had undemocratic

leaderships in all federal units.

Which couldn't get

along together.

And they managed to

stay afloat for 10 years.

The simultaneous decline

of the economy aside,

there was the indebtedness.

To begin with, they discovered that

the indebtedness already was huge.

We woke up after Tito's death

when things have just begun to unravel...

It took his heirs and his children

some time before they realised

that daddy was gone, that they

were now supposed to do something.

Then they slowly started

admitting our economic problems

into the public debate.

And then, all of a sudden,

the discovery of 20 billion dollars of debt.

It's still in a serious

order of magnitude.

But 20 billion dollars then,

dollars 32 years ago,

that was a complete shock.

Shortages began,

I don't know what...

So, the decline of

everyday life was palpable.

Could you tell us how you,

personally, dealt with these

shortages, coupons, the

odd-even driving restrictions?

I didn't drive a car.

I didn't care about that part.

And I had already heard something

about ecology and environmental concerns.

And I always thought:

the less cars driving around, the better.

I didn't care about

that at all.

But having a newborn child

and not knowing whether

you would be able to find

baby food and diapers.

Getting a paycheck or a fee,

which would be worth 40

per cent or 3 times less

the very next day in

foreign exchange bills.

It meant being on a constant hunt

for what could be obtained.

Coffee, butter,

like I said, things for the baby.

But such everyday things

like butter and coffee as well.

A frantic rushing to exchange

every dinar you got to foreign bills

to preserve its value.

It meant constantly

waiting in lines,

chasing foreign bill smugglers

around corners and all across the city,

waiting in lines in the banks.

One could really survive and

get by even in this hyperinflation,

but at the price of

a lot of work and a lot of time.

Hyperinflation was good

because it made all life on credit,

which endemically

existed in Yugoslavia

already since the second

half of the 1960s,

much easier.

Because the hard-currency clauses,

the reassessments of interests, etc.

Not even the banking system

managed to keep up.

And it wasn't allowed to,

for political reasons,

almost until the

end of Yugoslavia.

There was no radical

impoverishment then,

but, all of a sudden, we all had to deal

with economics on an obsessive level.

Things that were

supposed to be routine.

All of a sudden that

took up most of your time.

But the point is in the

political side of the story:

alongside all that, you have

a system incapable of making decisions,

whose protagonists, key building blocks,

are constantly attacking each other.

And consciously insisting on a competitive

position in relation to the others.

Croatia advocating this,

it's in Serbia's interest to do that,

Slovenia has other ideas, etc.

And they live together for 10 years.

Huh? How is that possible?

This is where the power of the

achieved nationalist identification

with a republic

showed itself.

Before they set out to

become independent countries.

It was in construction

since the late 1960s.

It had continuity.

Its constitutional acknowledgement was

its incorporation into the then regime.

Which was what had

allowed it to survive.

Not only while Tito played the arbiter

above the quarrelsome conglomerate

comprised of the leaders

of the future national states.

But even when

after he was gone.

And when they could reach

a consensus on one thing only.

Since they were all

undemocratically appointed,

which was how they

had come into power,

the only consensus they agreed on

was to watch each other's backs

against possible

discontent from below.

And that was frightfully powerful.

And that's where the

exceptional role of what

Slobodan Milošević

personifies comes from.

Because he went back to

what was tried out in Croatia in 1970 and 1971.

He went back to the

mass nationalist movement.

He merely called it

an Anti-bureaucratic revolution

to cover up this 'nationalist'

in the beginning.

But it emerged very soon

because of Kosovo.

You followed the political developments

in the other republics

on a federal level?

- Sure.

As far as media went,

since a relative

liberalisation was at work,

there were two excellent

newspapers.

One was the Belgrade daily

newspaper 'Politika',

and the other a Belgrade

weekly called 'Nin'.

It was the height of journalism

during Yugoslavia.

There you could see everything, not only

from Serbia, but from the other states.

Written quite professionally,

as much as it was possible at the time,

providing factual information

and coherent interpretations

on very many things.

And in the autumn of 1987 I realised

that something serious had happened,

after Milošević's triumph at the 8th Session

of the League of Communists of Serbia.

It was just like our

10th Session in February 1970.

Did you watch the live coverage?

- Yes, I did.

I recognised that something serious

had happened not only because

2 fractions had a quarrel

and one of them lost.

But because the winning

side was on the march,

on its way to totalise

its success through

everything that was

happening in society.

The Belgrade

'Politika' and 'Nin'

turned into rags

within a month or two.

Suddenly they were no longer

worth buying nor reading.

It was just one of the indicators

of what was happening.

Of course, plenty other

ugly things were taking place.

The symptomatic thing

about Milošević's movement

was that he had fallen out

of this common game

that kept them all in power through

arguments aimed at the public eye.

Not only did they stage their

arguments for the public,

but they really were at each

other's throats over resources

and political measures which

would suit one or the other side.

And, at the same time, they

had a nonaggression pact

as well as an agreement

on common defense

against the possible

rebellion from below.

Milošević fell out of it

because he had won the grass root

support of his lower echelons

through employing this

authoritarian nationalist matrix

that Savka Dapčević, and

Miko Tripalo and company

had staged the general

rehearsal for.

They chose

the wrong moment

because Tito was still

over their heads,

so they couldn't go

on with the show.

Milošević had a wide field

to take it all the way.

And enough unscrupulousness,

or determination and skill,

whatever people

choose to call it now,

to really make Serbia

the first separatist republic.

And not Slovenia or Croatia.

In the autumn of 1990,

a few months before

the democratic Constitution

was passed in Croatia...

You mean Christmas? - No, the Christmas one

was passed on the Day of the Yugoslav People's Army.

December 22. But, since

that was the last thing

that they wanted to tie

to this as a holiday,

they glued the holiday that

took place 3 days later onto it.

A few months before

this Constitution,

Serbia, under Milošević,

passed a Constitution

deeming Serbia an

independent national state.

But it also liked working

both sides of the street.

Because it still benefitted

from being in Yugoslavia.

Just like the Croatian Constitution

of December 1990 wasn't separatist yet.

And the Serbian

Constitution included

a deliberate absurd: Serbia

was an independent country,

but this was achieved

without leaving Yugoslavia.

However, Yugoslavian laws

were applicable only

if they didn't go against

the interests of Serbia.

They retained the freedom

of arbitrarily deciding

which laws would be implemented,

and which would not.

And this appearance of

Milošević as a national leader,

no longer relying on the

suport of the others,

but having his own

support from below,

caused panic.

And then the other leaders,

first of all, in Croatia and Serbia...

Granted, in Croatia the leaders

hesitated for a moment,

because they had

legitimacy issues.

They were inflicted

on Croatia after

the violent suppression of

the mass movement in 1971.

But there was no such

hesitatation in Slovenia.

But the political public in Croatia,

pushing its leaders to act,

talking about 'Croatian silence',

asking them to radicalise matters as well.

Upon the emergence

of Milošević's movement,

again manipulated

from above,

but apparently fuelled by

mass participation from below,

everyone reacts as if

it were a national menace.

Although there is no trace of any

endangerment of Slovenia, Croatia,

or anything like

that in 1987, 1988.

Slovenia was never even

threatened by Milošević's regime.

But he came in handy for them,

aiding their own nationalist mobilisation.

Because the pact of common

protection was now obviously failing.

He no longer needed them.

But they kept on

still playing that game.

It always takes longer for

all the consequences to sink in,

longer than it does for the

events themselves to take place.

Throughout the 1980s,

even with Milošević in power,

on the federal level, Serbia was

allowed to act as arbiter in Kosovo.

Regardless of the existence

of this incoherent system

through which the provinces,

that is, parts of a republic,

were at the same time

direct members of the Federation.

Did you follow, were you informed about

what happened in Kosovo in 1981?

Sure.

It was the talk of the town.

Everyone knew about

the demonstrations in 1981,

about Kosovo's claims for independence

as a republic, about the repression.

Information didn't circulate

through normal channels,

media couldn't send a reporter to the

scene and get some real information,

such a thing

was not possible.

But there were rumours, there were

always people who were better informed,

and we heard that about

900 people were killed

in the suppression of these

demonstrations in the early 1980s.

There was even a cruel joke.

At the same time, the Solidarity

movement was taking place.

In 1980, 1981, there were

rebellions in Poland.

And more suppression,

de facto a military coup, almost.

Calling it a military coup

would be wrong because

the Polish army didn't

act on its own,

it was carrying out

orders from Moscow.

9 people were killed in

the direct conflicts

between the army and the

people resisting them.

In Poland.

And the official news said

that in Kosovo in Yugoslavia,

in the beginning of 1980, 1981 at most,

9 people died as well.

And then there was this joke:

How many Albanians died in Kosovo?

Or, rather, as jokes are neither

politically nor morally correct,

the formulation was:

How many Shiptars died in Kosovo?

And it said: 9, but new ones.

What does 'new ones' mean?

In the economic reform,

in 1965 we had

a monetary reform

in which 1 dinar

replaced 100 old ones.

So that when you said something new,

it meant it was worth a 100 of the old ones.

9 Albanians were killed,

but new ones, which means 900.

That was how that joke

expressed that story as well.

Yes. We followed many things,

as much as was possible.

Besides, as a consequence of

this odd, ethnic pluralisation

during the 1980s, the media in Croatia,

and the media in Slovenia especially,

reported much more on

what was happening on Kosovo.

Much more than the

media in Serbia once

they had all fallen under

Milošević's control.

So that one could

access information.

Just to point something out:

although in Slovenia

the public had already

condemned the repression

used on those miners

who had shut themselves

in Stari Trg,

they had this

kind of suicidal strike,

the federal presidency still

allowed the army to intervene.

This reflex of suppressing and

preventing any revolt from below,

even if it was the enemy of

my enemy, was still strong.

The triumph of Milošević, who had

reached his position through formal means:

he became the Chairman of the League

of Communists of Serbia in 1986.

But he really assumed power after

the internal conflict in which he eliminated

the opposing fractions,

in the autumn of 1987.

And when he eliminated his predecessor

Ivan Stambolić, first from political life,

and 10 years or more after

that by taking his life.

On the one hand this meant

that the nonaggression and common

protection pact was disrupted.

But this change

didn't arrive overnight.

The system still worked

in such a way

that he was, from Croatia

and Slovenia, still granted the right to,

as far as the provinces were concerned,

alter the arrangements,

take away their autonomy.

And nobody disturbed him in this.

They even made official

decisions regarding Kosovo.

Because he couldn't have

the JNA at his disposal

for interventions without the

confirmation of the collective presidency.

They continued doing that.

Moreover, a sign that

they all favoured

the nationalist approach

because it allowed them to do whatever

they wanted in their backyards

could be distinguished

in their treatment of

these initiatives, present

until the end of 1988,

the democratic transformation

that was already in the air

and already seemed

unavoidable,

while, from our point of view,

it presented something

desirable and possible

for the regime.

From Slovenia, across Croatia to Serbia,

the same consensus

of Party leaderships

was still in operation,

dedicated not to allow democratic,

direct elections for the Federal Assembly.

Allowing democratisation,

democratic elections, pluralist, direct,

only in the republics.

The thought of having a democratically

legitimate supranational body

on the level of Yugoslavia,

that was...

Regardless of whether

they were bragging about

their great democratic qualities

as the Slovenians did,

or the Croatians,

a bit more shy about it,

or whether they had

this nationalist,

more of an authoritarian,

populist rhetoric

like in Serbia with its

Anti-bureaucratic revolution.

But they all calmly and

placidly agreed that

there mustn't be any

federal democratic elections.

You mentioned the factional clash

eliminating Stambolić and Dragiša Pavlović,

the effect of the Anti-bureaucratic revolution

in the provinces and Montenegro.

Seeing all that, did you think about

whether they were going to continue

their, so to say, march

in the other republics?

Everyone else was thinking about it,

so that my contribution wasn't required.

I was thinking about how they were

taking very good advantage of it

for a nationalist mobilisation

in Croatia and Slovenia.

Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina

were standing there a bit confused,

to put it in personified,

or personalised terms.

That's why I spoke of

their pact of mutual

protection at such length.

The so called people,

the crowd from below

was their common enemy.

Until Milošević managed to nationalistically

mobilise the populace for himself.

And becoming

independent of the others.

But there was no danger in that

for Croats, or Croatia and Slovenia.

But, when the complete breakup

of Yugoslavia was underway,

then Milošević had his chance,

since he had managed to win

over the JNA to his side.

Because he was, again,

smarter than the others.

He was the only one

to rhetorically advocate

the sustainment and

preservation of Yugoslavia.

And then his regime

saw a chance

to try and claim

whatever it could

of the territories of the

neighbouring republics,

that is, Croatia and

Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But his nationalist movement of

the so called Anti-bureaucratic revolution

posed a danger to Croatia and

Slovenia only in its nationalist ideology.

Not in any reality.

They mobilised everything they could,

as if the world was coming to an end,

as if they were facing

a coup in Slovenia,

when these nationalist

leaders from Kosovo

announced that they

were coming to Slovenia

to hold their so called

"truth rally" there.

The Mladina journal was the only

one that reacted cooly.

"What's that to us?

All they need to do is report

their desired location to the police.

And book rooms for themselves in the hotels.

That's their problem."

But the nationalist media,

which were the majority,

and the nationalist politicians,

once more, the majority,

with the support of the independent

cultural national intelligence,

as is always the

case around here,

made such an overblown circus out of it,

as if they were facing a threat

of being trampled over by an army

of a million zealous fighters

about to enslave the

whole of Slovenia.

They painted a

distorted picture.

And these very theatrics

testify to the ostensible threat

coming from Serbia at the time,

what we would

nowadays call a political spin,

but with extremely hard, palpable

consequences in the war later on.

Before we move on to the 1990s,

I'd like to ask you

whether you served in the JNA?

I did.

How did you

experience it?

Where did you serve?

When?

Fortunately, not too

far away from home.

I was stationed

in Benkovac.

It's on the railway line

from Zagreb to Zadar,

so I could sometimes travel home

without excessive complications.

And my wife and friends

came to visit me.

The experience was a

complete abominability.

I don't think I would

have felt very different

if they had sent me

to prison instead.

Having to be there

in that closed space.

I'm not referring to the containment

of 4 walls, but a closed space

surrounding you even when

you're under the open sky.

Kicked around by some

halfwitted squad leaders.

Doing pointless things, strenuous

and inconveniencing at that.

I was a bit older than customary

when I served the army.

It was in 1979. I was almost

26 and a half years old.

I potponed it for

as long as I could.

From a functional point of view,

it bordered on collapse.

Thinking that this creation could

ever have some kind of role

in, God forbid, defending

the country or anything like that.

I didn't think it would last any longer

than the Royal Yugoslav Army

did in the April War in 1941,

capitulating in less than 2 weeks.

Truly, the level of incompetence

in handling things...

I was in some kind of platoon

with a recoilless...

So, we had one of these,

as they called it, artillery pieces,

a weapon was something

one person could use,

a gun, pistol, bomb,

machine gun, mortar,

and this was an artillery piece,

a recoilless gun requiring a crew of 5 people.

In the end, one of the more sound

and educated officers told us its story.

It was an artillery piece that did

its share in the Korean war in 1951.

That was the last time

it was actually usable.

It was something

used against tanks.

It fired a missile similar

to the ones in mortars.

But it fired horizontally, that

is, aslant, as these things went.

And it was supposed to fight tanks because

it had this cummulative projectile

able to go through

their armour.

However, tanks, the speed

at which gun turrets moved,

the level of precision,

the sight and all that

had advanced so much

in these nearly 30 years,

28, 29 years since the Korean war.

And this one stayed as it was.

Heavy. To haul it anywhere,

transfer it from position to position,

all 4, 5 men had to pull

with all their might.

It was something

incredible, if you fired

it in some hypothetical

combat situation,

fired this missile

at the tank,

first of all, it was

recoilless because

it let out all those

exhaust gases behind it.

You created such fireworks

that you could be spotted out of

a satellite in the Earth's orbit.

Let's say you miss that tank,

or you hit one, but there are more,

they could set their sight on you

in 3 seconds and shower you with gunfire.

And you would barely have

the time to begin pulling it

into another trench,

a reserve position.

If this thing ever ended up

on an actual battle field,

you wouldn't need an enemy,

you would destroy yourself with it.

And there were many,

many other things like that.

Personally, I managed to get out of it

through having some typewriting skills.

So I escaped from the

infantry training to an office.

But then I saw an

interesting side of all this,

stemming from the fact

that I was in the army

at the same time that Tito

was dying in Ljubljana

during those 4 months,

after which he finally died.

So, I was sent to the army

in the autumn of 1979.

And I was discharged

in the summer of 1980.

I managed to scrape out

every possible reduction.

But I was able to observe all kinds of

things during these 4 months.

The first thing was the overwhelming

paranoia of the whole regime.

When my best friend returned from his leave

over the New Year of 1979 to 1980,

granted, he was in Velenje,

but he had stopped by in Ljubljana

before making

his journey back.

And the taxi driver told him that Tito,

after the New Year's celebration,

which was, I think,

in that hill near Kranj,

where he had one of those

presidential palaces, mansions,

he had been urgently taken to

the Ljubljana Clinical Centre.

He told him everyone was

in a state of panic.

As taxi drivers were already

equipped with radio transmitters,

they had a reputation for always

being better informed than others,

and passing on the

correct information.

So, he came to tell them

what happened to Tito.

And the media didn't release

it until a couple of days later,

reporting that Tito had

serious heath problems,

that he had to remain

in the hospital.

From that moment on we

were confined to the area

of the barracks, without

any rights of leave,

not only were the longer

visits home forbidden,

but the visits to

the town as well.

Thank goodness, there were no

mobile phones at the time,

so we couldn't feel the pain of

those being taken away as well.

But all the small radios and transistors

we had so we could listen to music,

the news, whatever we wanted,

I had one of them too, were taken away.

An order was issued

to collect all of them.

And store them in the

command headquarters.

We weren't dispossessed. We were

all supposed to get them back in the end.

But it was a signal

of panic for the army,

and they assumed we could be targeted by

enemy propaganda or who knows what.

Officers intensified

the on-duty measures.

Many of them, but not all of them,

slept in the barracks every night.

The regime they created

resembled war preparations,

as if we were about

to be attacked.

But there were

no real war preparations,

we didn't take out the

real battle armaments,

which were not used in

our stupid training,

we didn't have to take them

out of the storage depots,

reactivate them

or anything else.

They were just alarmed.

It was more of a political alert,

a sort of political alarm

that went on for months.

Which those of us in the army

experienced very traumatically.

Firstly, not being able to leave the

area of the barracks was awful.

It really intensified

the feeling of being in prison.

Secondly, the presence of the officers

in the barracks day and night was horrible.

Because of the general state of disarray

in the whole military institution,

which really gave the impression

that it was about to fall apart,

when the working hours of the officers

were over and they left,

only one stayed on duty.

But that one was somewhere getting drunk,

solving crosswords, phoning his lover

through the military telephone

exchange or God knows what else.

I've seen all of

these things happen.

But he doesn't get in the way.

And when the officers

are finally gone,

the regular life of the

barracks disappears.

When they leave, all of a sudden,

the rumpus begins.

Some brought hookers to the barracks

through the wire and fence.

Some used this same wire

or other holes in the wire to get out.

Those who were on good terms

with the storage workers and cooks

robbed the food supplies

in the evening,

throwing feasts

for themselves.

Using the supplies

intended for daily usage.

All in all, a sense of

freedom would reign.

With the officers inside,

all these things suddenly disappeared.

Then everybody had to

scrape along somehow.

And then one could overhear

many conversations.

From many conversations

with the officers,

as well as conversations

they had among themselves,

and I was a scribe, so

I was inside their office,

closer than

the other soldiers,

I gathered that, although

nobody had told them so explicitly,

no order was issued, there

was no political analysis

or piece of information

that they received,

but everybody understood that this

whole mobilisation was caused

by fear of something on the

inside, rather than the outside.

That was why, like I said,

we were not taking out any guns.

Because, according to their doctrine,

in Benkovac, we were the hinterland

of the coast,

of Zadar and so.

We were supposed to

be the front line

of defense in case of

NATO's seaborne attack

across the Adriatic,

from Italy.

That assignment was

in force for everyone,

from Istria in the north to

Montenegro in the south.

But there were

no military preparations.

Rather, they understood

that Tito's death

could mean a possible destabilisation

of the regime from the inside.

Some of these political things

were already noticeable.

What about the atmosphere

after Tito's death?

Well, then that...

Whatever your opinion of him was, it

was a shock and change for everyone.

Not really like fatherless children,

or, at least, not everyone.

But it was obvious that now

something was going to change.

Besides, we were deafened by

those commemorations, those things.

It lasted for a month,

two or three.

The only good thing

was the proclamation

of a week of national

mourning because then,

all of a sudden, they played

really great music on the radio.

This stupid pop music and

turbo folk came to an end.

They played serious,

classical music.

They played very

jovial things as well.

But, to people who don't like it,

all classical music is sad.

For example, you could hear a cheerful

Händel canatata or something of that sort.

But, no, it was all...

I culturally profited from Tito's

death through good radio program.

You can imagine what sort

of music they usually

played through the

barracks loudspeakers.

Predominantly turbo folk.

Up until then, I wasn't even

aware of the existence of that genre.

Before that,

I lived in another world.

And when he died, within the

barracks you couldn't hear anything

normal for quite a while.

Nothing but these

commemorative things.

The constant reading

of some speeches...

A competition in

ideological ardour

among all these officers and

noncommissioned officers was on as well.

Every troop, every platoon,

every last one of them

was writing letters to the

Presidency of the Party

assuring them we would

follow Tito's path.

And then they

read it in public...

We were on constant shock therapy

with an additional IV of ideology.

And then it all

settled down.

Then, I suppose,

everyone was so happy

because they realised that

the world hadn't ended,

that things were

somehow moving on.

By the time

these negative,

up until then, well hidden economic

matters started coming out,

I had already been

discharged from the army.

That story actually began sometime

at the end of 1980, the beginning of 1981.

The shock from the demonstrations

in Kosovo and the brutal suppression.

These things were

already out by then.

In the late 1980s or in 1990, 1991,

when did it occur to you that this breakup

of Yugoslavia, this desintegration,

was going to turn into a war?

It never occurred to me.

When it began, I still couldn't believe it.

I found it so absurd.

That's what happens when

things get too close

and you no longer

want to analyse them.

And you had an additional

resistance towards it

because every

nationalist paranoiac

says he saw it coming.

But not because he knew

it was going to happen,

rather, because nationalist paranoiacs

have to claim such things are coming.

Regardless of the real

state of affairs.

Like a broken clock that tells

the right time twice a day.

No. I was in utter disbelief.

Even when the JNA attacked some

of these posts in Slovenia.

It's wrong to call it an attack on

Slovenia, they were in Slovenia.

And Slovenia was a part

of their legitimate domain.

Even when it began, 2 days after

the declaration of independence,

on June 27, 1991,

I still thought it was just

a show of force,

some sort of incident, a quarrel that

was going to end in a political compromise.

Besides, in Croatia, the war

progressed at a snail's pace.

The war arrived slowly.

And there was a lot of

manipulation in the media.

Until mid-September,

Tuđman claimed

that the JNA was not the enemy,

the JNA wasn't going to attack us.

That it's all a misunderstanding,

ignited by these Serbian extremists here

and those installed from Serbia,

which was, granted, all true.

It's also true that

the JNA had no strategy.

It didn't give out any signals

of what it was up to.

If the JNA had a strategy

to gain control

over all of Croatia,

it wouldn't have withdrawn

from Karlovac.

That's one piece of knowledge

in military geography I acquired

while I was in the army.

Because some captain first class

wanted to take the exam for major.

And as this was during these

long days of sitting around

in the barracks

during Tito's dying,

he used me as a scribe to help

him prepare for his exam

in military geography.

Then I was able to read

many of their manuals.

And I learned that Karlovac

was the biggest garrison,

the place with the

largest concentration

of soldiers and equipment

in all of Yugoslavia.

The reason for this was that

Karlovac was the bulwark of defense.

In case of an invasion

from the East,

because nobody could stop those

tens of thousands of Soviet tanks

in the Pannonian Plain.

And the JNA strategy

had given up on using Zagreb

as the bulwark of the defense.

Generally, a big city is like a jungle,

a big city is a great seat of defense.

And they had given up on it because it

would mean the destruction of the city.

Nowadays, nationalists

would never concede that

the JNA took care

to spare their city.

At the price of

withdrawing further inland.

But, as Karlovac was where

the mountainous parts began,

and they, in line with partisan tradition,

loved forests and mountains,

then Karlovac would be the stronghold

of their defense on that side.

Additionally, in case of

an invasion from the West,

through Istria or

the Adriatic coast,

Karlovac would be close enough

as a background source

of reinforcements and

resources for those

who were holding the

first lines down below.

That's why Karlovac had such

an enormous concentration.

Which leads to the

conclusion that,

if the JNA had wanted to take

control over all of Croatia,

all it needed to do was

to sit tight in Karlovac.

There were more soldiers

than people there.

And it would have been like

putting a lock to the whole country.

The railway lines and roads between

the north and south of Croatia

pass through

Karlovac as well.

Since you were excluding the routes

through Bosnia and Herzegovina.

And there would have

been no way out.

Much indecisiveness

was involved in all of that.

I think that Tuđman's leadership,

Tuđman himself and everyone around him,

were going out on a limb with

the declaration of independence.

We'll just declare this.

A bluff, right?

And we'll see. Either they

won't dare to use force to stop us.

Or the West

will help us if they do.

Neither of the two happened.

Because they did use force to stop us,

since the JNA's ideology, doctrine,

policy and regulatory rules

legitimately made us its domain.

Just like Slovenia before us.

They didn't let go so easily.

The EU and the USA

never even dreamed of

burdening themselves with another war

on account of some batty nationalists

who wanted to play at

becoming independent.

They had no issues

with an integral Yugoslavia.

It wasn't a problem.

And being pulled into war

by nationalist gamblers,

well, they didn't admit

to that even when

it was obvious that

everything was going to hell.

They never took an active part in it

until 1995, when Clinton decided to,

as the saying went at the time,

get it out of the headlines.

We had a war

at a snail's pace.

Nobody really

acknowledged it.

The JNA didn't attempt to

subdue all of Croatia.

The Karlovac example

clearly demonstrates that.

It was operating along some

ethnic map of its own devising.

It decided where it wouldn't

get involved with Croatian forces,

the police and the new creation

of the Croatian National Guard,

and where it would put a

stop to their interventions.

They were obviously acting upon

their ethnically drawn lines.

The Croatian police

was able to

intervene in Pakrac.

It wasn't able

to intervene in Knin.

Because the JNA

wouldn't let them.

To this day they

can't agree on whether

the occupation of Vukovar,

where they dug themselves in

and destroyed everything for

3 months was necessary,

or they shold have

gone around it

and headed westwards.

To attack Osijek, or also go around it

and attack Zagreb, or not?

They were also

caught off guard by this.

The JNA paid the price for

being an ideologised army.

Functioning only

based on the presumption

of the reality

of what the regime

ideology was saying.

While the people were mostly

still in favour of Yugoslavia.

In the first couple of days

of the conflicts in Slovenia,

they were making

scandalised statements:

"My goodness, they have cut

off our bread delivery."

Or: "They have cut off our

electricity and water supply."

Well, you don't tell me.

And why wouldn't they?

When you acted as an

enemy, aggressive force.

No, they were certain that

the nationalist leadership

was manipulating the poor

people whose majority

was on the side of the

Army and Yugoslavia.

They didn't have

good political analyses.

Even before the war in 1991,

early on in 1991,

they came up with some

political proclamations

against these new

nationalist leaderships.

As if that was going to

actually work on anybody.

So, there were many excuses

for people like me,

who wouldn't believe that we were

truly dashing headlong into a war.

Because there were many

incomplete or ambiguous moves.

To put it in these terms.

You spoke of Milošević,

his politics, his intentions.

And how did you see Tuđmana and

his rhetorics, his rise to power?

Like pitch darkness.

He just used a new base of legitimacy

and returned us to the post-1945 era.

A revolutionary government